One of the reasons I travel is my always present desire to learn. To the end, history has always been a topic of interest for me. I will do the historic tours of locations and places. I benefit from learning the ways that politics, social conditions and reality-changing events influence the people in their locales. While history tends to be written by the victors, the places can still speak on the events that have happened there.

Only in the last few years I have been exposed to Texas, and my first visit to the state was accidentally as I missed a connection at IAH for my trip to Trinidad and Tobago for my cousin’s wedding. Since that overnight in 2006, I have returned to Texas nearly 10 times, including a recent unexpected overnight in IAH, yet again. (That just happened during my latest trip to a family wedding – the above-mentioned cousin’s father’s, a.k.a. my uncle’s wedding.)

A co-worker and I had to take a drive from Houston and to Dallas between our two events in Texas. Though the time between those two cities is around four hours, I had hoped to make a pit stop that would add another hour to the drive. Open to adventure, my colleague was amenable.

From Houston, we headed to the Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site via on US 290. From there, we took two different Texas State Routes until we made a left onto FM (Farm to Market) Road 1155. We passed simple wooden fences and saw a few sturdy homes, shortly after we saw a street sign indicating that we were entering Washington. Beyond the green street sign, there was a plain single story brick post office on the right and ahead of us was a market – small road-side place for groceries and to get a bite to eat. At the market, FM Road 1155 came to a T-intersection and headed to the right while to the left the road was blocked off. Still lined with modest homes and a few yards, the road continued due west and I saw the stone sign on the left showing the entrance to the Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site.

The woodsy and fresh smell of the cedar that I find to be scent of Texas was a light perfume in the air. Though it was mid-May, the day felt like the Fourth of July in Philadelphia: hot and humid. An appropriate though since we arrived at the Birthplace of Texas, Washington-on-the-Brazos.

I remember the Alamo and knew the names of James Bowie, David Crockett and William B. Travis. Yet, I didn’t know how this was a part of American history; I categorized it into bullets: Battle of the Alamo, Texas Republic and the Annexation of Texas, without any context to connect them. This visit helped shed light on the Texas Revolution and the history of the US.

Texas has its roots in its Spanish claim in 1519. Over 160 years later, navigational errors for a French exploration team lead them to Texas and to make a short-lived claim. After five years of disease and hardship lead the French to failure, Spanish expeditions located the abandoned French fort and reclaim Texas and Texas remains a part of New Spain for over 130 year. Yet as a part of New Spain, Texas is thrust into independence as a Mexican state, when on September 16, 1810, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Mexican priest, declared independence from the Spanish crown for the grievances of the Mexican-born Spanish and native groups against Spain during its war with Napoléon. (Note, this is Mexican Independence Day and has nothing to do with Cinco de Mayo.) The Mexican War for Independence ended in 1821 with the signing of the Treaty of Córdova.

The war against Spain left the Mexico bankrupt. In 1824, Mexico adopted a new constitution in which it established the state of Coahuila y Tejas, incorporating most of the present-day state of Texas within borders. The area of Tejas was very sparsely populated and settlers faced Apache and Comanche raids. Without any finances to support a military, Mexico encouraged settlers to create their own militias and enacted liberal immigration policies for the state in hopes that an influx of settlers could control the Indian raids. Stephen Austin was the first U.S. citizen to get a land grant, two years prior, to settle Coahuila y Tejas, near the mouth of the Brazos River, and soon after the Mexico adopts its new constitution the Old Three Hundred, the first sizable group of U.S. immigrants, settle in Tejas.

By 1830, the U.S.-born settlers, Texians, outnumbered the Mexican-born in the area of Tejas, and the Mexican President Bustamante implemented several measures to curb this growth. He prohibited further immigration from the United States to Tejas explicitly. Also, laws were changed to remove the tax-exemption for immigrants and to increase tariffs on U.S. good coming into Mexico. Lastly, Mexico had a federal prohibition against slavery and all Texian settlers were ordered to comply.

According to the Texas Historical Commission Historical Marker at the sight:

In 1835, as political differences with Mexico led toward war, the General Council (the insurgent Texas government) met in [Washington-on-the-Brazos]. Enterprising citizens then promoted the place as a site for the convention of 1836 and, as a “bonus,” provided a free meeting hall. Thus Texas’ Declaration of Independence came to be signed in a [sic] unfinished building owned by a gunsmith.

|

| Texas Historical Commission Historical Marker for Washington-on-the-Brazos |

The Convention of 1836, the Texas version of the Continental Congress, convened March 1 in Washington-on-the-Brazos to address the needs of the Texians. A week prior, President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s army arrived at the Alamo. Within the day, the delegates adopted the Texas Declaration of Independence and elected an interim government. The Republic of Texas was born, March 2, 1836. (So Texas is a Pisces, eh?) By March 6, the convention learned about the lengthy siege of the Alamo (yet, not knowing that the Alamo fell that very day), but Sam Houston, the future First President of Texas, successfully convinced the men to continue drafting new Texas constitution rather than rush to aid the soldiers. After the Alamo fell, Santa Anna's army marched towards Washington-on-the-Brazos.

The marker continues:

The provisional government of the Republic was also organized in Washington, but was removed, March 17, as news of the advancing Mexican army caused a general panic throughout the region. The townspeople fled too on March 20, 1836, in the “Runaway Scrape.”

After the Texan victory at San Jacinto, the town thrived for a period. It was again Capital of Texas, 1942-1845.

The Texas Congress permanently moved the Capital about 95 miles due west to Waterloo, TX, which was renamed Austin.

I never realized just how vulcanizing the Battle and Siege of the Alamo were for the Texians, but this is the typical story of the birth of national consciousness. This is the Texas equivalent of the Gallipoli campaign. The news of the Alamo is what determined Houston to make Texas a successful independence movement. With his signature, Houston turned Texians into Texans.

We stop in the Visitors Center to get oriented with the park and to find out which displays were the highlights of the site. We decided that the gunsmith’s unfinished building, Texas’ Independence Hall, and a walk to the Brazos would be the best use of our time.

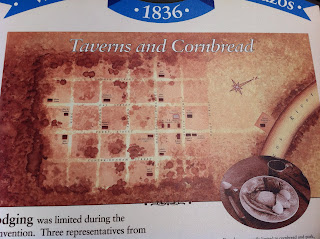

|

| A placard with a map of Washington-on-the-Brazos |

We followed the former Main/Houston/Market Street from the center into the townsite, and tried to beat a group of 2nd graders to Texas’ Independence Hall. Though we beat them into the Hall, we stayed around to eavesdrop on their docent’s story. The Hall is a replica, based on the text of letters from the Convention’s delegates. Regardless, on that spot, Texians forged themselves into Texans.

|

| Interior of Texas's Independence Hall |

|

| Exterior of Texas's Independence Hall |

We walked down the old Ferry Street to the river, and I turned around to look at Texas’ Independence Hall. It hit me how close the Historic Site is to the current town of Washington. That blocked off left turn in front of the market was at the end of my view of Ferry Street. I mentally overlaid the map of Washington-on-the-Brazos to the FM Road and realized that we took Preston Street into town and made a right onto Ferry Street, then traveled a few hundred feet before turning left to enter the park.

|

| The Rio Brazos |

At the site ferry station, I found the Brazos to be surprisingly deep, since I’m accustomed to the more easily forded spring-fed rivers of South Texas, like the Comal. Along the bank of the river, the volunteer told us about a pecan tree, which was present since the founding of the town. This tree is the tree that inspired the Texas Legislature to name the pecan tree as the state’s official tree.

|

| The Pecan Tree |

The end of our visit, I purchase some post cards to mail to my nephew, niece and their second cousins, like I usually do on a trip. As part of the transaction, I needed to give the cashier my zip code.

“One, nine, one…” I started to respond.

“Oh, wait, you’re not from Texas. We usually get zip codes starting with seven. Where are you from?” asked the female cashier.

“Philadelphia.”

“How are you making out in the heat?”

“It’s not bad; though it feels like more like a Philly summer than spring.”

“You don’t wanna be here in August, then. So, what are you doing down here?”

“Well, we’ve got one of these Independence Halls in our town and I wanted to see Texas’s.”

“Usually, things are bigger in Texas, but I hear that yours got ours beat.”

No comments:

Post a Comment